How Do I Learn Japanese?

20 minute read · Tue 29 MarchHow Do I Learn Japanese?

If you’re reading this, then you’re probably wondering how to get started learning Japanese. It can be tricky at first because Japanese uses different alphabets, Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji, and every so often all in the same sentence. I’ll aim to break your first steps down and the timeframes you can expect. These are just guides, and don’t get demotivated if things take slightly longer. Even Japanese people study for years and sometimes need to refresh their Kanji!

I’ll share my experiences learning Japanese in a university setting as a language-option alongside my main degree. That way, it’s still possible to learn what you need to learn alongside keeping up with a job or other studies. I’m not the sort of person who can devote all my time to just one thing (there are so many things I want to do!) so these methods worked for me, part-time, without driving me insane.

Yuki-sensei has devised a very efficient system to get you on your path to Japanese proficiency, but it still requires the work and time involved. The initial inertia of motivation will wear off, and it can be hard to keep going. If you have friends studying the language, that will help keep you motivated. We also have a community of students, all wanting to learn the same things! That’s what I liked about a classroom setting; we’re in it together, learning for a common goal. “Perfect practice makes perfect” my university professor would say, and it’s critical to do things correctly from the start, or you’ll find things harder down the line.

You don’t have to do anything you don’t want to. Learn at your pace, fit the lessons around your schedules. Test yourself when you feel confident and don’t worry about the speed of anyone else or trying to keep up in a classroom setting. Since Nihongo Life is online, we can take your feedback and make improvements quickly based on what is, and what isn’t, working for you.

Weeks 1-2: Learn Hiragana and Katakana

This is crucial! Learning Kana (that’s the general term for Hiragana and Katakana) is going to support your learning so much more than relying on Romaji. Romaji is where English (Latin) substitute Kana to make Japanese sounds. Romaji makes life very complicated and isn’t accurate enough to help with pronunciation or reading. And we don’t use it at Nihongo Life. So, it takes about two weeks to get to grips with Hiragana and Katakana. Actual Japanese students will spend months learning these by rote, writing them over and over. You don’t have to do it that way.

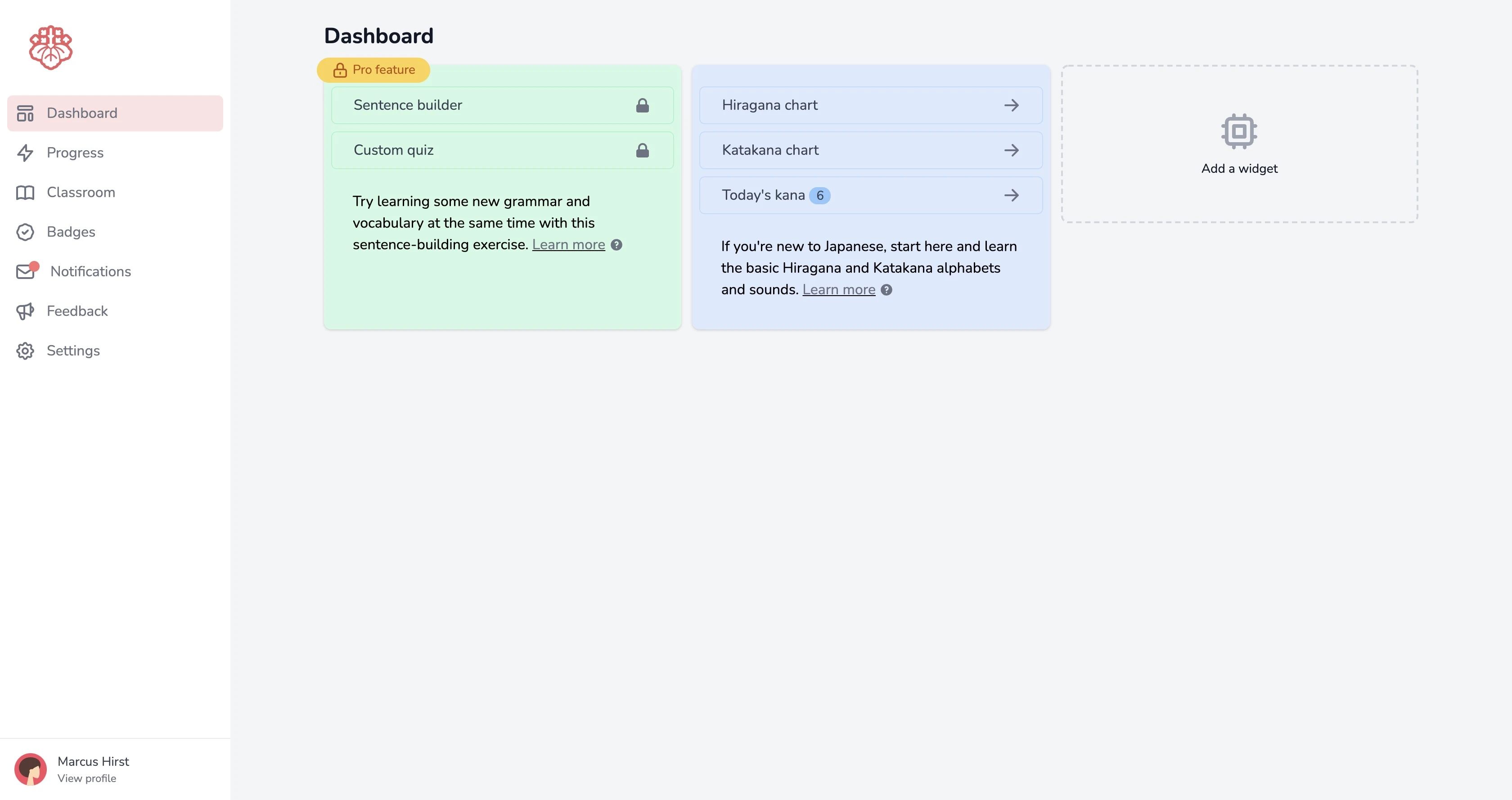

Kana makes the building blocks of sounds. Nihongo Life has a series of charts, audio, and articles to help you along the way. I’m a visual learner and used Dr. Moku’s Hiragana and Dr. Moku’s Katakana when starting out. These apps use mnemonics, to associate sounds with meanings and shapes. I will always remember that ”く” or “ku” looks like the open beak of a cuckoo bird. My professor set us a test at the end of the two weeks, and we had to get 80% or be kicked off the course… It certainly worked as motivation, and everyone passed. The formula to learn Kana isn’t too hard, it’s a consonant attached to one of five vowels. It can just be strange to get to grips with how to write it or remembering the shapes. But you can do it!

Spend your first day, to week, learning Hiragana. Then, when you’re ready, do the same with Katakana in your second week. Pay attention to the ‘Ra’ sounds, since the Japanese don’t have an ‘R’ like in English. It’s more like a cross between ‘R’ and ‘L’. Once you hear it, you’ll understand!

Week 2: Learn to type

In fact, unless you’re going to want to learn calligraphy; just use a keyboard. Learning to write with correct proportions and the stroke order is less important than conveying your meaning, and most text you see will be on a screen. Or you’ll be conversing, and then the written language is less essential. There are two mobile keyboards available natively, and we suggest the Japanese Romaji keyboard (OK, I said no Romaji, but here I lied). Hardly any people use the nine button Japanese Kana keyboard, and Japanese keyboards have Latin characters on them most of the time. There’s one ‘gotcha’ with Romaji keyboards, and you need to remember to press ん twice to get the character to appear.

Don’t get overzealous with allowing the keyboard to propose Kanji for you. Yuki-Sensei even finds this feature annoying at best since most of the time, it’s not what you want to type. The moral of the story is to stick with the Kanji that you know how to read. Press Esc to ignore the suggestions, or Tab to cycle through. We have Kanji on the iOS and web apps as a member feature. We also have plenty of videos out there with Kanji in context. As you learn, use whatever style suits you. Our Kanji White book is a good place to start.

Week 3-4 Get started with grammar

I found it best to focus on how to make sentences, and then build my grammar from there. The first sentence structure you’ll learn will be ◯◯◯は◇◇◇です。which means ‘◯◯◯ is ◇◇◇‘. Pretty simple? But you’ll build on that quickly. You’ll have vocabulary, particles (more on that later) and tenses. Try to keep your sentences simple. This helps you be clear with your intended meaning, and reduces the chances you’ll trip yourself up somewhere. Even something I heard in my more advanced classes from students was they would often try to use more complicated grammar structures when something more simple would suffice. We have many videos covering the subject on YouTube you can use and will help with pronunciation.

Week 4-7 Stop translating

When you get a bit more familiar with questions, ask them to yourself. I had classes once a week when we’d be paired up and had to ask each other about that week’s topic. Yuki-sensei’s approach is more direct and allows you to stop translating in your head. I was frustrated by language classes because I had the time to try to convert what was being asked of me in Japanese, to English, so I could form a reply in English and then translate it back into Japanese. This is so error-prone and an unreliable way to continue your studies. Yuki-sensei would ask me questions with ever-increasing speed, so I’d don’t have time to translate. It was very hard at first, but rapidly I began to stop thinking so much and actually responded in Japanese! Much like when I talk in English, you don’t think about it so much. We’d focus on vocabulary I had learnt. Adding か to the end of ◯◯◯は◇◇◇です makes it a question.

Yuki: 今日 は 月曜日 ですか。(Is today Monday?)

Me: いいえ、じゃありません。土曜日です。(No, it isn’t. It is Saturday)

Yuki: 明日は日曜日ですか。(Is tomorrow Sunday)

Me: はい、日曜日です。(Yes, it is Sunday)

And again, just with simple yes/no questions to build my speed, vocabulary, and comprehension quickly. Making these questions also lets you learn a few topics at once, like here we have ‘today’ and ‘tomorrow’ and the days of the week. So, it requires a bit of thinking.

Week 7-onwards: Kanji

Kanji work alongside Kana but carry meaning with them. It will take years to master, and Japanese people take years to learn Kanji. You need to know about 2,000 to read a newspaper. I probably know about \~150 well and can recognise the meaning of others but not the pronunciation, so I get the gist of a sentence when reading signs. You will pick up Kanji as you learn more words, and write more. Don’t focus on learning every *one* or *kun* reading as it can get boring and demotivating quickly. The best way to learn is when the Kanji comes up in a sentence you know how to read in Kana, or when you’re learning a new word you’ll use frequently.

My professor would make the class write essays every weekend. Which was tricky to fit in with my schedule, but made me better at writing in Japanese; they would be marked by the third-year students and would also offer corrections on proportions of written letters. The professors were focused on the pace. For example, we’d write わたし so often, and 私 is more efficient to write. However, every time I’d be asked to stick to the Kana, since we hadn’t properly looked at 私 until the second semester.

A lot of your time starting out will be looking up vocabulary or trying to remember what that Kanji looked like which you saw last week and now can’t remember whether it was on page 102 or in a different place altogether. I also keep a dictionary handy with the Midori app, so I can also write out Kanji if I don’t know how to spell it in Romaji or Kana. Using a study method called ‘Spaced Repetition’ allows you to get to grips with Kanji that bit faster and remember it a bit better than having to write it out repeatedly. It’s a method medical students use to remember all the terminology they need, and will help you when you face a plateau that many student reports after a year or two of learning Kanji. It’s also how the famous WaniKani will structure its study sessions, by showing you what you require, when you need it.

Keep going

We suggest keeping a diary. In Japanese. It doesn’t need to have long flowing entries, just a sentence or two. This will build a habit, so do it around another task you do every day. Such as after dinner or before bed. It’s a handy time to try out a new sentence structure, word, or Kanji you learnt that day. Keep learning and stockpiling your vocabulary. Kanji will follow as you become more and more comfortable learning words. If you get stuck, there are so many resources in the wild. Tofugu keep a well-curated list of anything new that appears. And it depends on how you learn best, but keep your end goal in mind. My weakness is that I’m much better at writing because then I have the time to sit and think about what I want to convey. But I can’t do the same when I’m speaking.

Getting Stuck

You’ll get stuck and usually face one of four bottlenecks

I feel that grammar is simpler to get past, since usually, you can break the sentence down into a few different structures. But it might feel frustrating that you can’t convey yourself as well as you would in English. I know this is in contrast with ‘your sentences are too short’. But best stuck to structures you know.

- You don’t know enough grammar

- You don’t know enough vocabulary

- Your sentences are very short

- You take too long to say things

I feel that grammar is simpler to get past, since usually, you can break the sentence down into a few different structures. But it might feel frustrating that you can’t convey yourself as well as you would in English. I know this is in contrast with ‘your sentences are too short’. But best stuck to structures you know.

Vocabulary you’ll kind of pickup as you need it. Which can be hard when you’re already saying something in conversation! If I realised I needed to say a word I didn’t know, I would preface my sentence with ‘◯◯◯は 日本語で 何 ですか。’ (What is ◯◯◯ in Japanese?). It’s a simple grammar structure like you’ve read earlier in this article, just with ‘what’ and ‘in Japanese’ in. Once I got the answer, I could then construct the sentence I wanted to speak -and usually the conversation partner would guess what I wanted to say when I asked for the word. I would keep a list of new words in the back of my notebook, so I could look them up when I had the time.

I’ve mentioned the last one before. Don’t. Translate. In. Your. Head. It takes too long, and it’s too easy to make mistakes. Default back to what you do know, make a note of what you were tying to say but couldn’t and study up on that!

Optional: Find a tutor or take a class

One-on-one time with a tutor at least once a week is a good way to learn quickly, since the course can be tailored to your progress. The tutor might also offer group classes, so you’re in a cohort of students who are at the same level. More conversation partners! Or take a blend of both. But a tutor is the best way, since you have someone confident enough in Japanese to be able to guide you as you get started and pick up on what you need to study. The downside will be the costs and any travel you have to make to get to the classes.

Don’t be afraid to leave the classes if the tutor isn’t working out for you. Teachers all have different styles and priorities, and every so often it just won’t be a good fit. A bit like dating. Say thank you (don’t ghost them!) Maybe offer some feedback and carry on with the search. It’s a professional relationship, and you’re the one in charge since you’re paying their fees. University and classroom setting are a bit different, since you don’t have much of a choice except to drop the class entirely if it’s not for you. And that’s OK. There’s not a time limit of when you need to learn something.

Optional: Taking the JLPT

The Japanese Language Proficiency Test is the ‘official’ way to have your skills graded if you want a stamp on your Resume. The JLPT isn’t prefect and focuses much more on comprehension than actual speaking, but it can be something to aim for and give yourself a deadline and an achievement when you pass! The exams come in five levels. N5 being the easiest to N1, the hardest.

These tests happen twice a year at registered test sites, and last a few hours. I’ll be honest, I like tests! Or at least the qualification you get from them. But if you don’t, that’s no problem. At all. It’s better to focus on what you want to do with your new language skills. If you hope to work in Japan, you may need a formalised qualification to demonstrate to employers you reached a standard they are familiar with; more common at larger enterprises. Otherwise, it’s more important you can get your meaning across, which is hard to express during a written exam.

Onwards: Intermediate Japanese

Was this article helpful?

Want to learn even more? Start your free Pro trial today.

You learn or relearn even faster and become more confident with a small time investment each day.

Start your free trial